Barrett The people who the people who have been caught up in this process, and that some sort of decision has been made that they're appealing. Who are these people and what are the kinds of decisions that are being made that they're appealing?

Emily They're citizens of B.C. and they are people who have been denied social assistance, disability assistance or child care subsidies. And so regular, regular people in B.C., many of them are some of the most vulnerable citizens in B.C., as you can imagine, dealing with social assistance and disability assistance.

Barrett What generated the concern? So this project is going on. There's the appeals tribunal and there's these clients who are able to appeal things. But something happened that said we need to do some research. What was the genesis of the project?

Emily Well, myself, I've been with the tribunal about five years now, not quite. And our director, Michael Doris, he's been with the tribunal about the same length of time. And we came to it fairly new when we started this project. We'd been there a couple of years and what we saw was a system that worked well. It got hearings done very quickly, but we heard a lot of complaints from appellants. There were lots of people complaining that they'd missed their hearings without knowing that they'd taken the place. Lots of anecdotal evidence from our staff that people were confused and didn't understand our processes. And, well, there'd been little process changes. We understood over the years the system had largely been created and it did a good job of getting things done. So there was no, no one thought there was a need to to really change things. And we looked at it and said, you know, with access to justice being at the forefront of things I'm passionate about. We're saying, how can we make it so we receive fewer complaints? How can we make the process less confusing for people? How can we focus on not what works for staff, but what works for the people? Everyday people who use our system. So I did a bit of a deep dive into accessibility and various barriers, systemic barriers that might be there. And what I realized was that I could have all sorts of really possibly good ideas, but I would have no idea if it was really what people wanted. I needed to hear from our appellants. What I really only heard from the appellants was angry complaints not useful information.

Barrett How did that turn into an interest in this Active Sensemaking narrative research that ended up using Spryng? How did that come about? And why not just do a survey?

Emily Why not do a survey? That's what I asked when I first heard about active sensemaking. And I guess I had gone to a seminar where the consultants we ended up working with Terry Miller. He was at this seminar and was showcasing what active sensemaking was about. And it really resonated with me because the tribunal had been sending out surveys, the user experience survey, with each of our final decisions and we were averaging getting about one or two back a year. So really they were telling us nothing. We would mail them out, we'd never see them again. No one took the time to complete them. And when Terry said, you know you can get people to share stories. Everybody likes to tell a story. That really resonated with me. I have an English degree. I love stories. I think words matter. And so that resonated with me. And I started to think about what we could find out from people's stories. And the more I researched and talked to Laurie Webster and Terry Miller, the more I realized that we serve this vulnerable population where people seldom at least, you know, people in positions of power over structures and procedures seldom ask for people's opinion. You know, we filled out surveys, tell us if you're unhappy. We know people are unhappy, but we don't know why. And we don't know what people's actual experiences are. We know that people who pick up the phone and yell at us. We don't know about the people who don't call. And so it dawned on me that doing active sensemaking could confirm some of the things we thought we knew, would let us know whether we were on the right track with suggested changes, could let us know where we might have missed the mark. But it would also tell us about what we didn't know we needed to ask about. And I think that's one of the places where the magic really lies is when you do a survey you're asking people to give specific information about things that you already have a sense about, you know. Tell us about how you like our computer interface. Tell us about how you found the hearing procedures. Were you satisfied or dissatisfied on a scale of 1 to 10? But by doing this, we were saying, tell us about an experience at the tribunal. And so. We heard all sorts of things we didn't know we needed to ask about.

Barrett Yeah, that's actually that's really the case. With the traditional survey, we have formed a hypothesis and we're testing that hypothesis, but we miss out on things that we might not have thought to test. And also the answers are all abstracted, so people give opinions, but we don't know the context of those opinions. And so what you're describing really fits and to be able to discover through stories, through the narratives that there's stuff we never would have thought of asking about, that suddenly looms up and we start seeing patterns of that sort of stuff.

Emily Absolutely.

Barrett Yeah. Yeah, that's really helpful. So tell us about the process of creating, you know, how did the instrument work, how did the methodology work and what were the sorts of questions you were asking people?

Emily The first part was coming up with an instrument that we felt and that our consultants felt would get usable data and usable experiences. And so we wanted to be open-ended enough that we were not doing what surveys do which is asking a preconceived question, but we wanted to and we didn't want to lead people into too negative or positive stories. So what we asked people to do was to start off by telling us a story using one of a number of different prompts and an example that we used that I think we got the most response for was "Tell us about a time you felt respected or disrespected at the tribunal." And another prompt was "Tell us about a time when things worked well at the tribunal or tell us about a time when things didn't work well for you at the tribunal." So very, very open ended.

Barrett Those are brilliant because there's no right or wrong answer. I mean, you can't game those questions.

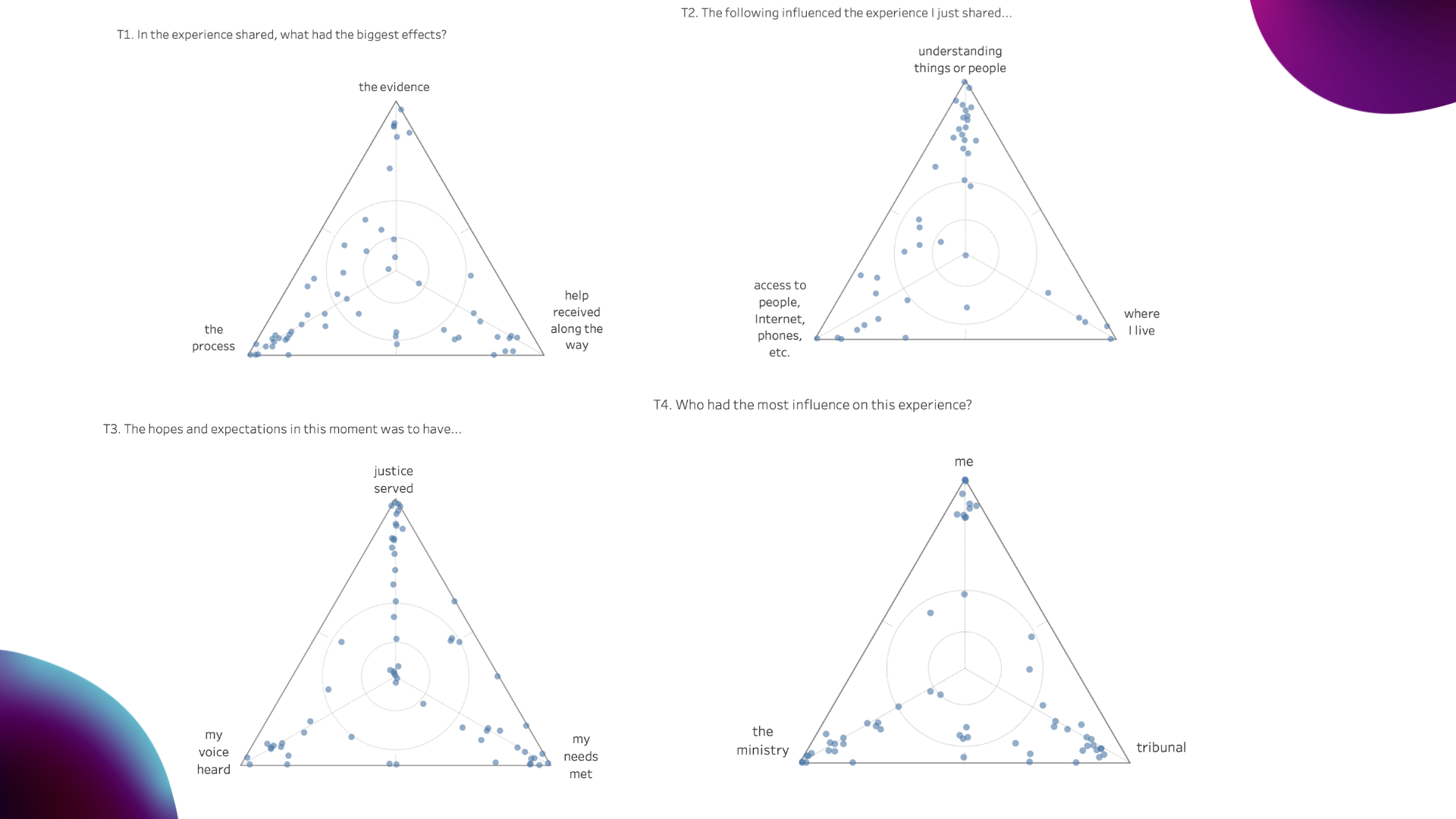

Emily And we also designed it with the view that we were one of the first people in the administrative law sector that we knew of doing this work, that some of our colleagues might be able to take those questions themselves and use them in the future. So we wanted to make it broad enough that the work we were using might be able to be useful to other people and that it wasn't daunting. When you ask someone to tell us about a time, tell us about your thoughts about our rules of practice and procedure, you know, that's difficult to understand. You might not know what our rules of practice and procedure are, but tell us about a time things at the tribunal worked well for you. It didn't work well for you. Every one of the people who have come to our door will be able to think of something in their heads. And so we asked individuals to provide that story. And then the next part was to give that story a title. And the titles were quite telling. Some of them too much paper confusion abounds. Things like that, but I see you giggling. We had a chuckle at some of them, but they really hit home and you could see the tone that you were going to get. And then from the story, there were some follow up questions and the follow up questions asked people to signify their own data. Was this a positive experience or a negative experience? And we asked them to do that, to remove our personal biases from understanding the story. You know, there's some examples, and I can't think of them right now, but ones where - it looked like it might be more negative from the story title, but it actually was a positive story and a positive experience for the user that it turns out that there were lots of phone calls and it turns out that was helpful because it meant that there was a real person that they could connect with. It wasn't that there were too many phone calls, and so they signified it. And then we asked them we had these little triangle questions with sliders, where somewhere on the triangle we asked them to mark. What impacted their stories? Was it primarily, I think one of the choices was that primarily the tribunal, the processes and procedures or the ministry whose decisions we adjudicate. We included that one because we knew a lot of people confuse us with the ministry and they might have a complaint about the ministry that that isn't us or they might be really happy with the ministry, but not happy with us. So we wanted a way to screen out those or to pass those complaints along to the ministry and let them know what we've learned. We also asked people about what helps with looking at the sliders, you know - was it technology? Was it where they were located? So the users could provide their own signification about what was important about their story and what they wanted us to know about it. We also had some follow up demographic data about where in the province they lived, roughly what age group they were in. You know, cultural backgrounds, whether individuals identified as indigenous so that we'd be able to look and see if barriers have been reported, were they barriers that affected everybody, were they barriers that were affecting a particular group, whether it was gender or ethnicity, we'd be able to look for hidden systemic barriers.

Barrett Yeah, actually, I mean, what you're describing, people are invited to share story and there's no right or wrong story. You know, good or bad, share a good story or a bad story. So share a story and experience an anecdote. And then they interpret that story. They tell what it meant for them, how they you know, how they processed it by asking some questions that are interpretive questions about that story. And then with the demographic questions you're able to see, are there patterns that emerged through these stories and do those patterns relate to demographics or how do they relate to other aspects of data that emerge through the process. And so you end up exploring the pattern, and it's really interesting. You said that when you'd sent out surveys in the past, you might get one a year. I'm presuming you got more than one of these back. How did that process work?

Emily With a huge amount of terror on my part, because we had paid to put and to establish this process. And so we started creating the instrument and then we had to test the instrument to see if it worked. What we did to test the instrument was to call a few of our appellants that had used our system in the last few months and asked if they'd be willing to be guinea pigs and our appeal coordinators of staff that had worked with them before, asked them to complete the instrument. And so they were willing to. And we recognized that it worked. And we got stories back and then we had to go live with it. And I was really scared because what if we had spent money and taken a lot of staff time to create this project and we made it go live and nobody responded. Or I got two responses, one up from our survey. When it went live, I was terrified. I thought, oh, no, oh no. Oh, no. Because historically we weren't getting surveys back. We weren't getting feedback back. People are living in, dealing with trauma. They've got much higher needs than letting Emily in her tribunal know how they feel about us. They're worried about, you know, food, shelter, rent, you know, big, important things. But we went live and we started to get data almost instantly. We emailed, sent the link out to the data collection platform with a little paragraph from me inviting appellants and explaining why we wanted to do this. And I think within 5 minutes of pressing send, I received a number of emails saying, Wow, no one's ever wanted to know what I thought before, especially not about a government service or about my experience with something like this that really matters to me, you know? Going through this whole process matters to me. But no one's ever taken the time. It was actually a bit emotional to read some of these emails because people were excited to be asked. People were calling us and saying, I don't have a computer or you know, I don't have the ability to do this. Is there someone who could help me with language? How can we do that? I want to be part of this and we received more than a statistical sample back. We went in, asked everyone who used our services, at least the appellants in the last three years, and we got a nice solid statistical sample back. And people actually asked, will we be doing it again? I think I got one of those emails not too long ago, so. It was very different. No pulling teeth. People were willing to share.

Barrett Wow, Yeah, well, you know, there is something. Distinct. I think about that, what you're just describing, because we always get these customer feedback forms. You know, I get several a day, typically from any interaction that I've done with various retailers and service providers, and they say, you know, your opinion is really valuable to us. But in actual fact, the minute I enter that, it's not my opinion, it's just some massive data somewhere they don't - my story has gone.

Barrett I just think about what you're saying. I'm really delighted to hear you explain that, because I think that's true. When it's done well, when it's done the way that you did it, in reflecting your values, that you're very clear about it, saying these are human beings whose experiences matter, their stories matter. And we actually do want to hear your stories.

Emily And the email that went to all of our users and appellants made that clear. It said, you know, we're looking at our processes and our procedures and how people experience the tribunal, and we were wanting to use your experiences to make changes, to make things better for the people who come after you. Yeah. Hearing that I think resonated with it. You know, all of these people had received the survey, None of them. One of them had responded.

Barrett What did you learn through this that you might not otherwise have learned as you look back at this point?

Emily You know, learned about our processes. Sort of data feedback is that what your.

Barrett] The whole that about the process actually about the methodology. But I'm thinking about – I was actually thinking about the data that you got back that, you know, you've done this you've had people have interpreted you've gotten a good response. But anything that comes to mind in terms of that question, as you look back and think about what did we learn about this? What stands out to you?

Emily Well, I think we found out a lot of things we didn't know we needed to ask about. And I think what we also found out was that sometimes the things that really matter or mattered to our users were things that we would have thought of were tiny or inconsequential. The changes that we've ended up making are all very, very small. Other than redoing our website, none of them have had really a monetary price tag attached to it. They've been small, insignificant process changes. I shouldn't call them insignificant because to our users they're clearly not insignificant. They're things that we sort of thought were insignificant. I look at examples, know an example that I like to use is - we always ask - Quite often the ministry will want to bring an observer to a hearing for training purposes. Doesn't surprise anyone that that happens? Really routine? We would say yes, but you need to have the appellant's consent to have that party there. And so everyone would come to the hearing and whether it was on video or telephone or in person and the panel hearing the appeal and we adjudicate with a panel of three, would ask the appellant if they consent to the observer being there and the appellant would often consent. Sometimes they wouldn't. And if they didn't, the observer would have to leave. And what we got back was a very telling and emotional story about an individual who pointed out the very real power dynamics in that situation. You know we thought we were asking for consent. No one's there who the appellant doesn't consent to. But they pointed out how they felt nervous going into a hearing. Their future on assistance was up for debate. There was monetary consequence for them at the end of the hearing, and the panel that was going to make the decision was asking them for a favor. They saw it as a favor, not as consent to let this person sit in. And they didn't want to let the person sit in because they hadn't mentally prepared to have them there. The ministry representative of the panel, and they thought two people for the ministry, I feel comfortable they're ganging up on me. But they didn't feel comfortable saying no. And so they said, like everyone would probably say, of course, no problem. They didn't want to seem difficult. The appellant did the hearing with this extra person in the room having to hear the information, and a lot of the information that is given as evidence for our hearings is deeply personal. It's people's financial records and their personal medical histories. And so they had this extra person in the room that they didn't want there, but they had felt, if I say no to the people who are deciding my fate. That doesn't look good. I want these people to like me. I want to be seen to be agreeable. And so when we looked at that story, it became blatantly obvious. And like, you're nodding as I say this because it's blatantly obvious there's a power imbalance. The wrong time to ask. Super, crystal clear. We just had never taken the time to put ourselves into the appellants shoes for that. And as soon as we read it, we were like, of course. And there's a really simple solution. We had the appeal coordinator call the appellant. They're not the one making the decision. The appellant's already familiar with this individual, and they say, look, you can consent or you can say No. Either one's fine. They do it a couple of days before the hearing, and people quite often say no now. They sometimes say yes to, but we get informed consent and there's no surprises when the person gets to the hearing. Everybody they expected to be there is there. And there's one less thing to be nervous about. So that yeah, really obvious. Not the type of information that's earth shattering, but makes a huge difference to people coming through our processes.

Barrett Yeah. It's a brilliant example. And it's precisely the sort of thing that you would catch in a narrative capture, sharing stories and interpreting them that might be very hard to catch otherwise.

Emily Another great example we got was an individual who pointed out that the hearing room and I should say we use hearing rooms all around the province wherever we can book a room because we don't have offices everywhere - looked out at a police station and the individual had a history with a history of trauma and looking at the police station exacerbated that. And they felt, you know, why couldn't we have closed the curtains? Why couldn't we have made someone else look out the window? Nothing, nothing, nothing that requires a big change. We didn't have to book it someplace else. But now we look out the window when we see what will the person sitting here will look at, and we come to it with a trauma informed lens and say. All right. If there's a police station or maybe there's an ambulance facility or, you know, a homeless shelter or something like that, we take that into account.

Barrett Those are really excellent, really excellent examples. And just a little bit more about the process. So you've, you've explained what the issues were that sort of generated the, the decision to use the active sensemaking and then a little bit how you created the instrument and then you got invited people to participate and people participated and then you get all this data back. What did you do once you got all the results? How did you incorporate that and pull out the lessons, tease out the lessons or the insights from the data?

Emily Well, what I wanted was for our consultants to hand me the data and give me the stories that captured the stories. Here you go. Take it and read it. That's how I thought it would happen. They said, no, you need to go through the sensemaking portion of making sense of the data. And my colleagues and I sort of rolled our eyes and said, This is ridiculous. This is a waste of staff, time and resources. They wanted us to come to a number of different meetings with our team and have everyone look at bits and pieces of the data and start mapping it. So it was during the pandemic, we couldn't do it in person on a whiteboard. So we used whiteboard apps and things like that to group like data together and start sifting through the, not the stories, but some of the titles and some of the metrics that we'd received. And we did a couple of workshops doing that and then we did a couple more sort of few other workshops where we went through the stories themselves and grouped them and then took the titles and made our own new titles to sort of make sense of the data that we had received. I had to eat my words because it was not a waste of time. Having our whole team work through the data together made it so that by the end of the first workshop - my staff was suggesting process changes because they had heard from appellants and heard a narrative story which sort of tugs at your heartstrings. And they wanted to make the process better. They wanted to change how we do things to solve these problems. And for me as a leader, it was really interesting to see that because I can tell people and have been telling people for years, you know, nobody likes a complicated process. We need to write things in plain language. And people didn't jump at the chance to make process changes when I said that. But when they heard stories from people in their own words and started to look at the data and recognize, well, they're grouping like stories with like this isn't just a one off, there's another one over here. And, you know, it became a bit of a running commentary. Oh, look, here's another in the too much paper pile. You know, the too much paper pile now has too much paper in it because we kept shoving things into that group. The process itself was sort of the change management needed to shift the workplace culture from a culture of let's get things done, let's do things like we've always done. We do a good job, we're fast, we're speedy to really want. Let's put the user at the center and let's do whatever we can to make the experience of being an appellant at our tribunal better for those people.

Emily People started to address the initial stories, but now, you know, it's been a year and a half later and our staff is - I'm still having bi weekly meetings where they go around a round table and say. What did you experience this week? What did you find where an appellant had an issue? How could we make that better? And so it's now sort of a ground up process change. You know, it's continual and the whole office is wanting to make things better.

Barrett We make sense of the world through stories. I could wax on a long time, but that's how we do it. And if we can, if we can stay there for a little bit, to tease them out, to play with them, to learn from them. It's a very human way of engaging with change, engaging with systems and bringing about improvement. And it's really fun to listen to you describe it.

Emily Well, it was unbelievable to be part of. And yeah, the power of stories - I've long believed in the power of words, and hearing what someone says about how it affected them personally. It's so much different than getting a two or three on a ten bar scale of how your services are.You know, that sucks. It's not pleasant, but you don't necessarily feel motivated to make it better for this person.

Barrett Well, I mean, you think about it, you know, and when you're in the break room or wherever it is, we meet some friends at a coffee shop and they say, So how's your day going? None of us says, Well, today's the 3.50 yeah, well, a 4.7. I'm I was, I was a 4.2 yesterday, but today's a 4.7. We said, Oh yeah. And we tell stories. I mean we, I mean it's really crazy that we think that, that 4.7 is saying very much actually.

Emily Yeah absolutely.

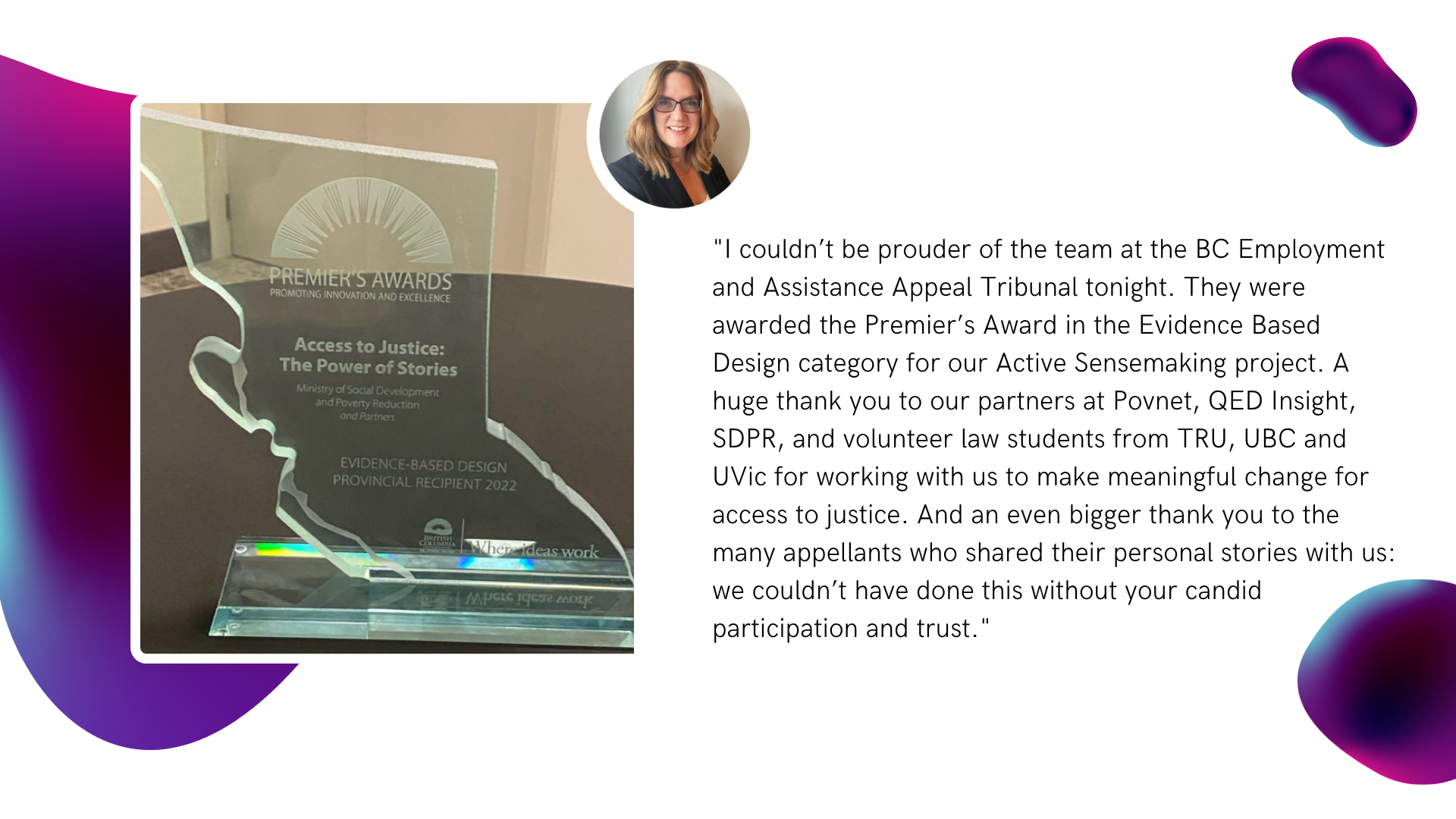

Barrett And you guys won an award. Tell me about the Premier's Awards.

Emily We did. We were nominated for our work in B.C. Premier's Awards. They have a number of different categories every year to highlight the work of the B.C. public service. And we were nominated -

Emily in the evidence based design category. So they were looking for people who are making evidence based or evidence informed programs or policy development or. Procedural changes based on evidence. So not just deciding that something needs to happen for another reason, but doing it based on evidence. And so we were nominated in that category and we had some steep competition because there's all sorts of interesting work being done in the province and we were fortunate enough to win. Which is really, really nice for our team because we've worked really hard on the project and it's taken, like I said, it's changed our workplace culture and it's made people have to do things differently. And so to be recognized for that work and being seen that yeah, that the changes that we're making and the time and effort staff have put into making those changes really makes a difference and that other people think it makes a difference. But I think people think it's worthwhile work.

Barrett Yeah. Yeah. Well, I mean, you've described. You know your initial reasoning for doing this kind of project and what the outcome of it is that your clients, your appellants have felt like their voices mattered and they felt honored and taken seriously through the process. And their concerns and issues. Their needs have been taken seriously. And your staff, I mean, I'm really intrigued by your staff sitting around and reacting differently. Being able to put them more likely to put themselves into the place of the people that they serve.

Emily Yeah. I really think that the magic it created with our staff. Is one of – I wasn't expecting it at all. Like I said, I was like, why do we have to sit and map all this together? Just give me the stack of stories. I think that's really, you know, other than getting the user experience from individuals. That's the most valuable portion is the transformation it made for the workplace. It really shifted the culture.

Barrett Yeah. Yeah. No, that's. That's really impressive. Now, you said that you were hoping that this might be a model, or at least some parts of it could be useful to other agencies. You created the instrument in a way that it could be adapted with the, you know, the prompting questions and that sort of thing. But if you were to give advice, if you were if others were coming to you saying. Should we use this? What kind of advice or what kind of suggestions might you make?

Emily Well, first of all,I'd say absolutely. I think we give ourselves too much credit when we assume that we know best and don't ask what our users experience. And sometimes that user experience just reaffirms that we're on the right track, but sometimes it points up glaring errors. And like I said earlier, sometimes it shows you what you didn't know you needed to know about. So absolutely, people should do it. There were some challenges along the way, though, and I think people need to know that they're going to face some of these road bumps. The biggest one we had was, I guess we had two big, huge challenges in the process. And one of them was that the instrument is electronic, digital. It's on a computer and that's where data gets inputted. But 30% of our users report not having access to computers or cellphones. And so. We originally gave our consultants that statistic and they went, Oh, we can't just get data from the people who have computers or else you're going to have, you know, biased data. You're not going to get user experience from the people who you might really need to hear from. And the normal way, apparently, of crossing that divide is you gather go out and bring people to come in person to some sort of workshop where they would share these stories and that data would be entered. But we were having the second challenge was all of this was done during the pandemic. And we think the part of a pandemic where we were working from home and not seeing our neighbors and so. How are we going to get data from users who didn't have access to technology when it was a digital platform? We thought, well, we have regular postal mail and we have telephone. And that is how we communicate with our appellants who don't have access to email or computers. And so we came up with this idea. I was told it probably wouldn't work. It seems unlikely to be successful, I think what our consultant said was don't get your hopes up. We might not be able to do this until after the pandemic. My thought was that what we should do is call the people who don't have email and invite, explain what we're doing and invite them to take part in the process. And if they said yes, we would mail them the printouts of the paper instrument. We call it the paper instrument because it was our paper instrument. It was the digital printout on three pages of paper, and we would mail that to them and then we would schedule a follow up phone call at the same time that we told them we were going to mail it to them with someone who would walk them through the form on paper and input their answers into a computer as they walked them through the paper form. And then we tested that with some of our - I said earlier we did some test audience and we tested the paper instrument. And lo and behold, people were actually able to give us data that way. And it worked. But then we realized that 30% of our appellants for the last three years was going to be hundreds of phone calls and our staff actually has the business of running appeals and scheduling things and we also knew that to be statistically accurate and get good data we shouldn't have staff being the ones who are asking the questions because they have preconceived relationships with these individuals. So we reached out to the three faculties of law in the province Thompson Rivers University, UBC and University of Victoria, and asked their administrative law classes for volunteers who might be interested in working with us. And we got a number of volunteers, and they met with our consultants and they learned all about the instrument and the methodology. And then they went to work contacting all of the appellants. They divided it up. So each had a long list and they spent a few weeks of their lives contacting these appellants. They'd let us know back at the office. We've got a yes mail out the paper instrument. And then about ten days later, after the instrument had arrived in the mail, they call again at a scheduled time and they walked the appellant through the instrument and input their data for them. And so. No one thought it would work, but we were able to use really low tech solutions to bridge that digital divide. And that was the type of solution that people without computers were used to. It wasn't difficult to ask them to deal with mail or telephone because that's what they're used to.

Barrett That's that's really it's very impressive. I would have been among those who would have suggested that it probably won't work. So.

Emily I mean, in hindsight, I think it might have actually, for our particular population. Maybe that works better than getting people together in a workshop group because they're scattered all around the province. People might not have wanted to come together and had sort of that group experience. But one person on the phone taking the time to spend some time with them to hear what they wanted to say and really just being a transcriber.

Barrett I can see that. I mean, having to gather someplace means I have to actually make an appointment. I have to go somewhere. And vulnerable people. That means what? They have to take a bus or who knows how they manage to get to wherever that's going to be. And then there's other dynamics with the, you know, the folks gathering together that have to be managed. Whereas the phone call, I'm actually saying with a phone call, you matter. I'm here to get your voice. I want your perspective. I want your story. And I actually think, you know, in hindsight, reflecting on it, I can see why. It worked. Why it was powerful. And you're right. It's a low tech way, but it's that in itself, the process itself is taking seriously the reality of those people's lives.

Emily And there were some changes we had to make. The triangle question with the little slider. You can't slide something on paper, and it's very hard to say. The upper right hand corner of a triangle. But the result is that we worked with, did a brilliant job, and decided they would]break the triangle down into a bunch of number grids and so on the paper instrument rather than a slider where you could put a dot anywhere in a triangle people could say over there in space number four, or up there in space, number ten. And so the person on the other side of the phone knew exactly where in the triangle they wanted that.

Barrett Yeah, that's a brilliant solution. Very impressive. Very impressive. Kudos to you guys.

Emily Another neat side effect of having law students volunteer is they report that they learned a lot about access to justice and a lot about systemic barriers. More so than they would get necessarily from a textbook explaining what they got. You know, you can often go all the way through law school without talking to an actual person who uses the system. You might not you don't get clients and often you don't get. Clients. Until you've been a lawyer for a couple of years, you might do research projects and things for other people, but they got first hand interaction and to hear some of these stories. A few of our students actually said it changed their outlook on law and it changed their outlook on what they might want to do with their career. So like a total partnership win all around.

Barrett Wins all the way around.

Barrett Was there any anybody that you had to convince any sort of naysayers in the system? If so, how did you bring them around?

Emily There were people who thought - I don't think they said it right out loud, but you could tell that they thought this might be a waste of resources and time. You know, we already know what needs to change. We need to simplify things. It's confusing. We already know what has to happen. So why do we need to find that out again. And I think the way we got around that was really to include everybody in the process. And I didn't mention it when I talked about the development of the instrument. We included our whole team. Everybody in the office got to be part of going and working with the consultants to figure out what questions to ask to talk about our experiences. We had a representative from the ministry whose decisions we adjudicate. They came and they were part of it and we had a representative from POB Net, an organization here in D.C. that provides a network of advocates who provide legal legal advocacy for people who don't have lawyers or need help with things. And so we had someone representing the appellate needs. We had someone representing the ministry, and we all worked through it and having everybody involved. It wasn't if it was just me doing it, it wouldn't have the same value by having everyone working together through the process. People were convinced that they saw it as it was unfolding, that, hey, this is working.

Barrett It's interesting. So that actually from the very beginning, there's a process of collaboration and there's a process of co-creation in which the voices of all the various participants, the various stakeholders at that end of it are contributing to the outcome.

Emily Absolutely.

Barrett Actually modeling the very thing that it's designed to do with your appellants. And it's also being modeled at the front end in the creation of the instrument and the creation of the strategy to to get the data.

Emily We plan on doing this again. We've got lots of good feedback and we have ongoing process improvements happening, but some of our changes that we've made might have missed the mark we might have done things and they might have created new problems for people or made a change that created a barrier for another group of individuals.So our hope is that every three years we can do this project so that we can compare the data and we can see are we having - one of the rankings was how positive was your story that you told or the experience that you shared - in a trend towards more positive stories versus more negative stories when people think of us and are asked, tell us about a time they're - hopefully with time it was largely negative. But I guess that's another challenge. It's a bit scary to start a project that is going to publicly create a record that people are unhappy with the services that you provide. When you get data from survey results, you can kind of stick those in a file and not. But when you spend money on something like this and people know you're doing it, it takes a bit of courage, I think, from my team to put ourselves out there and say, Hey, we're willing to be critiqued and we're willing to let people know that yeah, what we were doing and the services we were offered weren't, you know, there were lots of problems.

Barrett There's a little bit of human nature in that. When I've worked with clients, I always would tell them – expect that the negative side will outweigh the positive side, because by human nature we have evolved and we are wired to notice the problems more than we notice the good things.

Emily We also found out things that we're doing that worked really well and that people liked and knew. All right. People think having our appeal coordinators, being friendly and talking to them and being a person, they can call with questions. They like that. So we should do more of that. So now we include a business card and a little introductory phone call that says, Hi, I'm your appeal coordinator and I'm here to help you through the process.

Barrett Wow.

Emily I don't understand why everybody doesn't have an active sensemaking budget, because I know other colleagues who do user experience, but in different ways. But getting the actual narrative is just so impactful.

In this interview with Emily Drown, learn how the BC Appeals Tribunal used Active Sensemaking to improve their processes and experiences for appellants.

Introduction

Emily Drown is the chair of British Columbia's Employment and Assistance Appeal Tribunal.

It is an adjudicative tribunal that hears appeals of denials of certain ministry decisions, particularly decisions related to denial of social assistance or disability assistance or child care subsidies. People have an opportunity to seek reconsideration from the ministry. And if they still aren't satisfied with the decision, they can appeal it to the tribunal, and the tribunal will hear those appeals.

The Employment and Assistance Appeal Tribunal wanted to improve the experience for others going through their appeals process.

Why Active Sensemaking? Why not just use a survey?

“The tribunal had been sending out the user experience survey, with each of our final decisions and we were averaging getting about one or two back a year. So really they were telling us nothing. We would mail them out, we'd never see them again. No one took the time to complete them.”

“I've long believed in the power of words, and hearing what someone says about how it affected them personally. It's so much different than getting a two or three on a ten bar scale of how your services are.”

“I've long believed in the power of words, and hearing what someone says about how it affected them personally. It's so much different than getting a two or three on a ten bar scale of how your services are.”

People like to share stories. What could we find out from people’s stories?

Bridging the Barrier

Learn how Emily, her team, and consultants bridged the barrier of how to provide the opportunity to appellants to share their experiences.

We plan to do it again.

Emily and her team plan to do the Active Sensemaking project again in three years. With their process improvements based on user experiences from the project, they hope to see a trend in positive experiences.

Should others use Active Sensemaking?

Q: If others were coming to you saying --

Q: If others were coming to you saying --

"Should we use this?" What would you say?

A: I would say, “Absolutely.”

I think we give ourselves too much credit when we assume that we know best and don't ask what our users experience.

Sometimes that user experience just reaffirms that we're on the right track, but sometimes it points out glaring errors.

Sometimes it shows you what you didn't know you needed to know about.

Premier's Awards: Promoting Innovation & Excellence Recipient

Emily and her team won the Premier's Award, in the Evidence Based Design category for their Active Sensemaking project.

I don't understand why everybody doesn't have an Active Sensemaking budget, because I know other colleagues who do user experience, but in different ways. But getting the actual narrative is just so impactful.

Learn the platform and Active Sensemaking, a free Video Course with your subscription to Spryng.

Learn the platform and Active Sensemaking, a free Video Course with your subscription to Spryng.